Egypt is a massive living organism — a web of ticking clocks, each set to a slightly different millisecond. With approximately 80 million in the country, 18 million of whom are woven into the streets and buildings of Cairo, the traffic of the city may crawl but many would say it is only by the will of God that it continues to flow at all. People are everywhere — driving, jumping off buses, walking, bicycling … ticking minute by minute through the days and nights of the city. Doctors, valets, belly dancers and beggars … Cairo keeps 18 million cogs in one of the world’s busiest wheels. This series takes a magnifying glass to one person, a representative of a job that keeps the city ticking — an eye-level shot that takes you through a day in the life of a cog in the wheel of Cairo. —Nevine El Shabrawy

“BEKYA!..” shouts Amin Mahmoud as he pedals his cart slowly down a dusty Agouza street scattered with trees. “Bekya!” he shouts again in that nasal tone so distinct and known you’d think they’d all taken a class.

“Enough! People are trying to sleep!” interjects an angry woman from her apartment window.

“Bekya!” Mahmoud responds undauntedly, before joking in a quieter voice: “She wants to sleep and I want to eat; life is all about compromise.”

Mahmoud, 30, has been a robabekya — junk — trader since 2004, when financial hardships forced him to quit his beloved job as an Arabic teacher. Some of his friends were working in the business, owning a storage space and some carts; the money sounded appealing, so he opted to join.

But Mahmoud is quick to needlessly explain: “This job is not at my social level, I have a college degree,” he says, requesting that his photo not be published.

I tell him that work is work, and that it’s nothing to be ashamed of, to which he responds: “My extended family back home [Assiut] still thinks I am a teacher. It’s a nicer image — everyone is happier this way.”

Mahmoud’s social concerns aside, he comes off as motivated and accepting when doing his work, and is well-liked among the various people we pass, save for the odd angry housewife still sleeping at noon.

On an average day, Mahmoud will wake up at 9 am in his house on Faisal Street in Haram, where he lives with his wife and his son Moataz, who is 2.

“There’s no reason to get up earlier, people aren’t in the mood for sales at 8 am,” he says.

While getting ready he’ll decide on a general area to work in for the day.

“There’s no set route,” he says. “I’ll go through various areas where I know people, or take routes I like that make me happy, or I’ll center the day around someone who has called me to sell their stuff.”

This day’s route includes various parts of Agouza, Dokki and Mohandiseen. I met Amin on Battal Ahmed Street near the 6th of October Bridge ramp at around 11 am on a Thursday. His bekya-mobile is rented from a network of bekya friends for about LE100 a month. I proceed to walk by his side as he pedals into Agouza.

“Bekya!” he bellows, until the first person stops him, about 20 min after moving off of Battal Ahmed. It’s a doorman, trying to rid of some books for one of the building’s residents. Mahmoud gives LE5 to the doorman for a handful of old, torn books.

When asked about how he feels about his days, Mahmoud says: “I ride, and I wait, and I enjoy the trees. I stick to quiet streets and I try to keep myself peaceful,” he says, before again shouting, “BEKYA!”

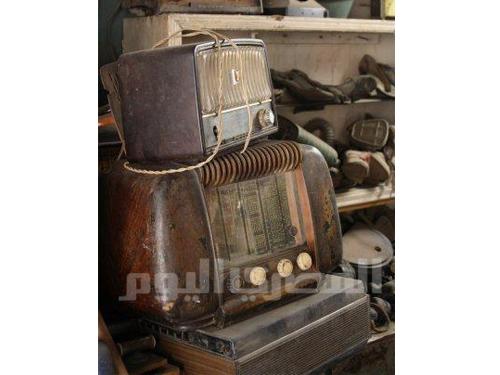

At times it feels as if Mahmoud suffers from a unique form of bekya-flavored Tourette’s syndrome that he’s long come to accept. Over the course of the day, he stops about a couple dozen times to negotiate with various people looking to sell their junk. Some chairs, an old washing machine, magazines, TV remotes, dress shirts, lamps and cutlery are among the items offered to Mahmoud on this day.

“I’ll take anything if the price is right — it’s my job to not be picky, but also not get ripped off,” he says.

Many of the customers already know Mahmoud, and the deals are usually simple, smooth and friendly. But he says this is not always the case.

“Of course there are bad people, like with everything else in life, right?” he says.

After prodding for some examples, which he is reluctant to give, he says: “[Yaani] For example, you could get drug addicts trying to sell other people’s stuff, always looking to make an exact amount. At first I was a bit unprepared for that, but experience and knowing your neighborhood helps.”

Embarrassed, but with a slight grin, Mahmoud recounts a time a couple of years ago when a young man in his early 20s was quickly trying to sell him a ring, supposedly for drugs.

“After, a man came running out shouting, ‘You son of a bitch!’ and chased him off with a belt!” says Mahmoud, followed by nods and a sorry smile.

He later learned that the older man — to whom the ring belonged — was the young man’s father, and Mahmoud was later requested to never buy anything from him again. Others may try to sell Mahmoud fake china or designer bags, often “swearing to God that they are genuine.”

But overall, Amin admits that “stuff like that happens, but I can’t say it’s the norm. Most people are good and use the service the way they should. But sometimes prices are hard to agree upon.”

By now Mahmoud is peddling back over Battal Ahmed into the Dokki and Mohandiseen. “Bekya!” he shouts again. It’s about 2 pm.

Mahmoud believes that robabekya trading has had better days.

“People used to sell silverware and quality items,” he says. “But around 2008 that stopped. I don’t know if people are getting stingier or going broke. Everyone’s afraid for their finances now, I think.”

Mahmoud works about four to five days a week. He usually works until about 4 pm, when the traffic starts getting heavier, and only takes one proper break to pray. He doesn’t eat from breakfast until dinner when he returns home.

Throughout the day, he runs into various acquaintances — semi-actively — and often stops for cigarette breaks and general chitchat about someone nearby wanting to get rid of something.

“I think someone on the next block wants to get rid of a nice couch,” says a doorman at one point. Amin doesn’t respond, though you can tell he acknowledged the information by the curious forward gazing expression he exhibits while exhaling cigarette smoke.

At one such break, we discuss the presidential race. Mahmoud had intended to vote for Hazem Abu Ismail but was been turned off by his behavior after his recent cut from the race.

“If you’re out, you’re out,” he says. “This sit-in business is disgraceful.”

Mahmoud now intends to vote for Abdel Moneim Abouel Fotouh or Mohamed Morsy, “either or, I don’t know yet, but absolutely no one from the old regime, like Amr Moussa or Ahmed Shafiq.”

It’s almost 4 pm, and we’re in Dokki by Sudan Street. Mahmoud says that his day is done, followed by another, “Bekya!”

His next job requires taking all his findings from the day to a storage garage near his house in Haram that is shared by several robabekya runners. Mahmoud says that selling items day by day is too time-consuming and doesn’t pay well, and that bulk sales are better.

“We collect everything there for about two to three months, and then we invite buyers to the lot and have a big sale,” he says.

However, net profit appears to remain uncertain.

“You have to be careful how you spend your money — three months could produce LE5,000, or it could produce LE500. Depends on your luck.”

When Mahmoud was getting married, he said he collected all the domestic goods and furniture and put them in his house as a gift from his work colleagues.

“I also still tutor private Arabic lessons when I can for extra money,” he says. “I really love teaching, and hope that someday it will be my full-time job again.”

At about 5:30 pm, Mahmoud has reached his house, and parked and locked his cart in an adjacent alley. He’s looking forward to having dinner with his family at about 8 pm and relaxing for the rest of the evening.